With the atrocities of the Holocaust brought firmly back to the forefront of our attention this week, it’s important for us to remember the millions of victims who suffered at the hands of evil during one of the most horrific parts of World War 2.

Our Holocaust Remembered tour follows the moving story of Anne Frank as well as the story of Oskar Schindler. Our specialist guide, Charlotte Czyzyk, who also works at the IWM North, specialises in the Holocaust, and here talks us through some of the most moving and thought provoking aspects of this emotional tour.

The Holocaust Remembered – Charlotte Czyzyk

This tour covers the history of the Holocaust in which 6 million Jewish men, women and children were murdered, as well as countless others because of their race, religion, sexuality, nationality, or disability. We follow the footsteps of those whose lives were affected by persecution, and include testimony from individuals such as Anne Frank to bring our excursions to life. We visit beautiful, vibrant cities where Jewish culture thrived before the war, including Berlin, Krakow and Prague, which reminds us of everything that was lost in the Holocaust.

We see the traces of Nazi architecture in the German capital of Berlin, and visit the villa outside the city where senior Nazis held the Wannsee Conference in January 1942. This secret meeting sealed the fate of European Jews, and it is always striking to think that such a beautiful lakeside location could provide the setting for such cold and calculated decision to murder millions of people. We also visit one of the earliest concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, where barracks have been preserved to gain a sense of the prisoners’ daily life.

Moving onto Poland we walk through the sites of the former Krakow ghetto and Plaszow concentration camp, which during the war were plagued by overcrowding, violence, hunger and squalor. Later in the tour we also visit the so-called ‘model ghetto’ at Theresienstadt near Prague, which deceived the Red Cross inspectors into thinking that conditions were acceptable for the people held there.

For many passengers, visiting the former concentration and death camp at Auschwitz is a particularly emotional experience. Seeing the huge displays of confiscated belongings – shoes, spectacles, even women’s hair – is overwhelming, and it helps us to begin to come to terms with the human tragedy that unfolded there. The remains of the vast death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, including the railway lines, prisoner barracks and gas chambers, show how the Nazi machine was geared to destroying people using industrial methods.

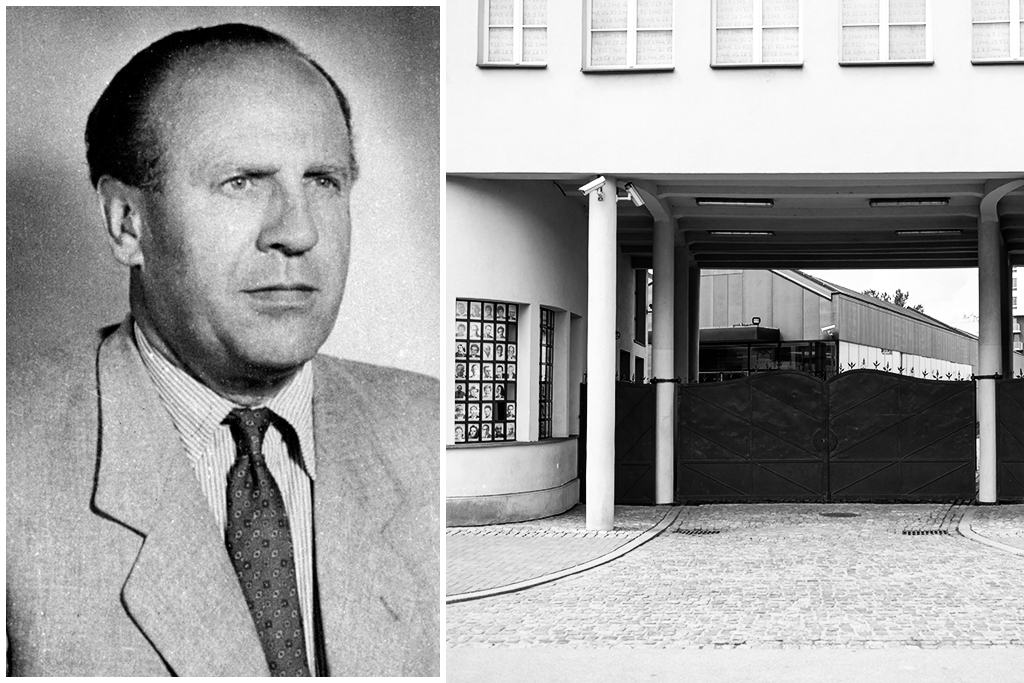

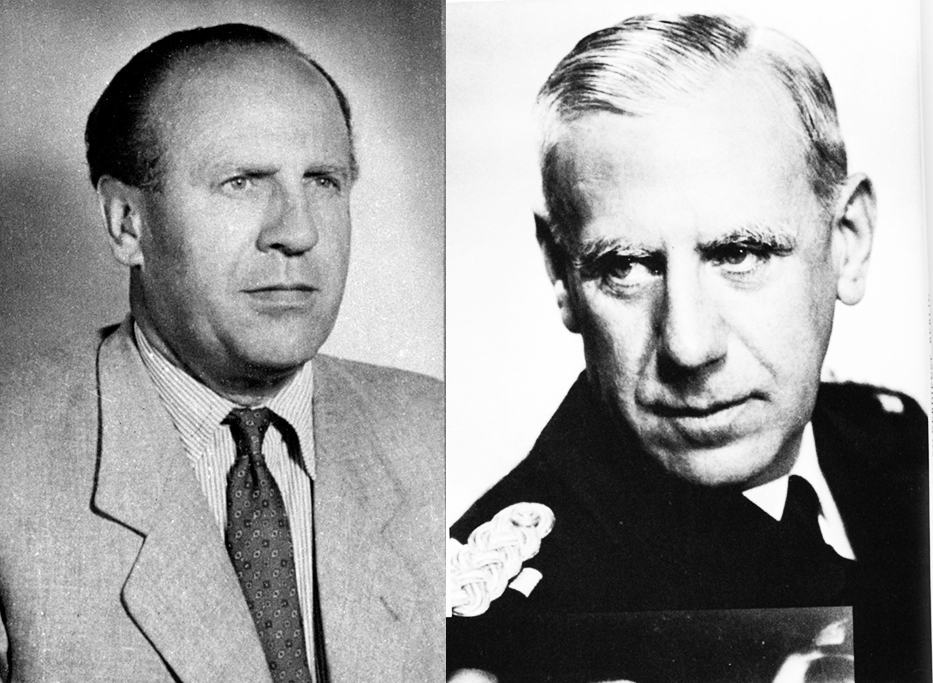

And yet amongst the suffering and loss, there are tales of hope and courage. We look at stories of inspirational individuals such as Oskar Schindler, and visit the museum at his former factory in Krakow where he employed and saved 1,200 Jews. We also move to the Czech Republic to see the church in Prague where the brave assassins of SS leader Reinhard Heydrich met their fate, a building which still bears scars from the fighting that took place there over 70 years ago.

The end of the war created new challenges for survivors. We visit the former concentration camp at Bergen Belsen, which was liberated by the British Army in April 1945. At this emotive site we think about the difficulties that soldiers faced in providing the food, clothing, and medical assistance required to save as many people as possible, as well as the psychological support needed to help survivors to make sense of all they had come through and all they had lost. Some people poured their efforts into seeking justice from the perpetrators, and we end the tour by visiting the Nuremberg courtroom where the trials of leading Nazis such as Herman Goering took place.

This tour follows journeys of many kinds: journeys of death in trains, in ghettos and in camps; journeys of escape, hiding and survival; and journeys made after liberation to a new life. I hope that you will join this special trip to unforgettable sites, which create evocative memories for all those who travel with us. Click here to view WW2 Battlefield Tours.